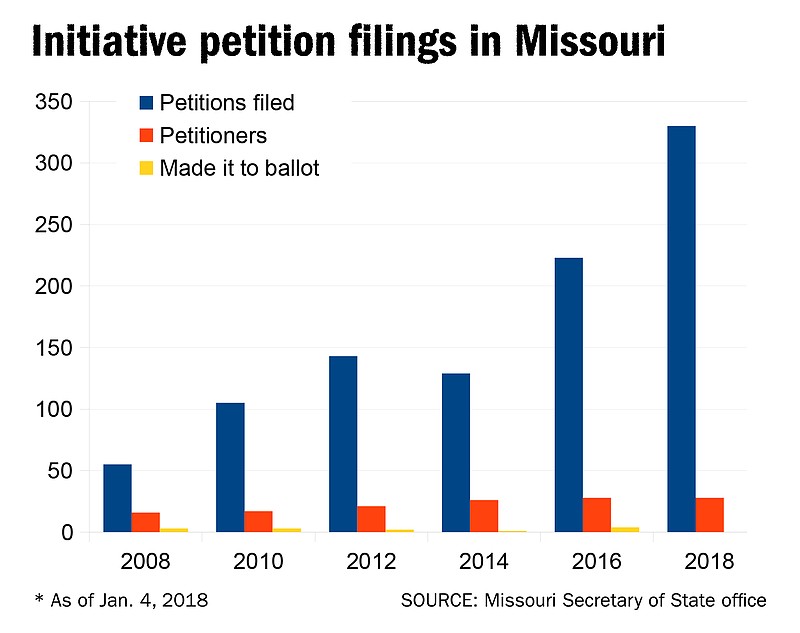

For the fourth time in the last five election cycles, the Missouri secretary of state's office has handled a record number of initiative petitions, and the current petitions cycle still has three months to go.

As of Jan. 31, when two more petitions were turned in, 349 petitions had been submitted for processing - a more than 50 percent increase over the 223 proposals submitted during the 2015-16 election cycle when Jason Kander was secretary of state.

Of those new proposals, 190 seek to change the Missouri Constitution, while 159 aim at changing state laws.

The proposals cover a variety of subjects, including legalizing marijuana, changing Missouri's minimum wage, requiring paid sick leave for employees, changing the Legislature's operations, modifying election laws and changing court operations.

If past trends repeat themselves, Secretary of State Jay Ashcroft said last week, only a handful - maybe five or seven - will be on a statewide ballot later this year.

According to research by the National Conference of State Legislatures, Missouri is one of 19 states that allow people to propose a change to statutes and/or the constitution and place that proposal directly on a state ballot.

The right has been part of Missouri's Constitution since at least 1875, with the current language saying: "The people reserve power to propose and enact or reject laws and amendments to the constitution by the initiative, independent of the general assembly, and also reserve power to approve or reject by referendum any act of the general assembly."

The referendum process was used last year after lawmakers passed and Gov. Eric Greitens signed a right-to-work law, blocking it from going into effect unless voters statewide endorse it.

Jay Ashcroft, in his second year as Missouri's secretary of state, said there could be several reasons the initiative has grown more popular in recent years.

"In the last 20 years - a little bit less - you've seen a very big change, shift, in the politics of the Missouri Legislature," he noted. "Twenty years ago it was Democrat-controlled; now you have super-majorities of Republicans. So I think there are definitely individuals who would have moved things through the Legislature before that are now saying, 'We can't get those through a Republican legislature.'"

But, Ashcroft added, there also is a growing number of "national and outside groups that are trying to get changes across the country, (and) the initiative petition process is a way for them to go ahead and do that," especially if lawmakers have rebuffed their efforts to make changes through the General Assembly.

Processing petitions

Although the Missouri Constitution gives people the right to submit initiative petitions, state law dictates a process that must be followed.

A person or group with the idea must submit their proposed petition to the secretary of state before they can circulate it to gather signatures.

Under current law, they can submit a proposal beginning the day after the November general election in even-numbered years - and must submit their completed petitions, with the required signatures, no later than six months before the November general election.

This year, the petitions are due May 6.

The law also requires petitions to be submitted with signatures from registered voters in at least six of Missouri's eight congressional districts - with a minimum of valid signatures from each district equivalent to 5 percent of the number of votes cast for governor in the most recent election (right now, 2016) for a law change, and 8 percent of the votes cast for governor for a constitutional amendment.

But, before supporters can circulate a petition to gather signatures, the secretary of state's staff must review the proposal to make sure it follows the mandated legal form.

Among the requirements is that the proposal have the full and correct text of the change being sought, including "all matter which is to be deleted" from the current statutes or constitutional language and all new matter.

The secretary of state is required to write a "summary statement of the measure which shall be a concise statement not exceeding 100 words (not counting adjectives). This statement shall be in the form of a question, using language neither intentionally argumentative nor likely to create prejudice either for or against the proposed measure."

Ashcroft said: "Sometimes I think it's impossible to do one that fully, completely, clearly and without bias explains" the proposal.

He noted his office received one petition with 47 pages of proposed legal changes, "so we had just under two words per page to explain it."

Ashcroft didn't identify the specific proposal because he said he didn't want to appear to be commenting on it.

"But I don't think there's a good way to really educate people (about an issue) with two words per page," he said.

He supports a change in the law that would allow the secretary of state more words for the ballot summary.

"We want everyone to read a petition," Ashcroft said, "but I think it's pretty clearly understood that a lot of people don't, unfortunately" - relying, instead, on the secretary's ballot summary.

The courts have ruled over the years that the summary does not have to be - and, in only 100 words, cannot be - inclusive of every issue contained in a petition.

"We don't want to write a page for people to read either," he said. "It needs to be simple. It needs to be concise, complete and fair."

The attorney general's office also reviews the petition and the secretary of state's summary for compliance with the legal requirements.

Ashcroft said 14 different people on his staff alone play a role in the review work.

The 'vetting' process

The state auditor's staff must prepare a fiscal note predicting how the proposed change will affect the financial operations of state and local governments.

The vetting process doesn't guarantee a proposal wins approval to be circulated.

Although 163 proposals so far have been approved for circulation, 21 were submitted then withdrawn, and 163 were rejected.

"We've had petitions where there were verbs missing (and we) couldn't figure out what they meant," Ashcroft said. "You don't want the law like that - especially if it's going to be in the Constitution."

He said his staff has reached out to supporters to explain a rejection so they can fix their proposal and re-submit it.

"We're not going to reject it because we don't like what you want to do," Ashcroft said, noting his office is supposed to remain impartial on election matters. "But if we can't even understand what the (proposal) would do, then we're going to say, 'Look, you need to make this clearer so we can write a ballot title for it.'"

Ashcroft would like the law changed so his staff can question a proposal's constitutionality when it first is submitted rather than waiting, as the current law requires, until the signatures have been gathered.

"If they didn't meet the Constitution when they turned in the signatures, they didn't meet the Constitution when they first turned (the proposal) in," he argued. "We should tell people as quickly as possible so if they want, they can change it. Or if they think we're wrong, they can challenge us in court."

Handling multiple petitions

One issue raised in recent years is petition supporters submit multiple versions of the same idea with different language in each version.

As an example, supporters of a fuels tax increase could propose asking voters to approve a 5-cent increase, or an 8-cent increase, or a dime increase in the current fuels tax.

Because the law requires each petition to be specific, that example would result in three different petitions being submitted with each one processed separately.

"If you're really trying to change our Constitution (or our statutes), you should really figure out what you want the wording to be before you're submitting them," Ashcroft said. "It ought to be well thought out and planned. I think what it really comes down to is people submit multiple versions because they're trying to see what the ballot language will look like - and my concern with that is it looks like you're trying to 'game' the system."

Ashcroft also would like to see the current law changed so petitions could not be filed in the weeks after the presidential election - when Missouri's secretary of state also is on the ballot - to avoid a situation where an outgoing secretary could rush the process before the new secretary was sworn in to office.

In a six-page brochure showing his priorities for this year's General Assembly, Ashcroft reported Secretary of State Robin Carnahan's office handled only 55 petitions in the 2007-08 election cycle, with only three gathering enough signatures to appear on the 2008 ballot.

And only a handful of people have been responsible for submitting petitions.

In the 2007-08 election cycle, the 55 petitions were submitted by 16 individuals.

In the 2009-10 cycle, the number of petitions submitted almost doubled to 105 - again with only three making it to the 2010 ballot and only 17 different people submitting them.

In the 2011-12 cycle, 21 sponsors submitted a total of 143 petitions - and only two were on the 2012 ballot.

In the 2013-14 cycle, Kander's first year as secretary of state, the number of submitted petitions dropped slightly to 129, submitted by 26 people - and only one was on the ballot.

And in the last two cycles, 28 people have submitted all the petitions - 223 in 2015-16 and 349 so far in 2017-18.

"I think we have one person who's filed 60 (or) 70 petitions," Ashcroft said. "And what I think a lot of people don't realize is the work that has to go in once a petition is filed."

Ashcroft supports a change in the law that would let him charge a supporter for each petition submitted with an extra charge if the petition is longer than 10 pages. The fee would be refunded if the proposal actually was placed on the ballot.

"I don't think that we ought to tax people" for submitting petitions, he explained. "But I don't agree that the people of the state should be required to subsidize your ideas for initiative petitions."

He noted the current law allows people to submit a proposal as late as April this year - even though that's too late for a proposal to clear the review process and have time to gather signatures and still submit a completed petition by May 6.

It generally takes two or three years for the General Assembly to consider, debate, modify, rewrite and modify again a proposed law before it gets passed.

Some complain the initiative petition process avoids that lengthy debate but also results in laws or amendments that haven't had enough debate or tweaking.

"If you have several million dollars to spend, you can almost completely control the narrative," Ashcroft said. "There's really no public debate. You generally don't get a whole lot of newspaper or television coverage; it's not like something is debated in the Legislature.

"You already know what your messaging is going to be. You're already getting the word out as to why people should vote in the way that you desire - the opposition, if there is any, has to look at what you're trying to do, try to get people together then raise the funds and figure out what their message is."

Ideally, Ashcroft said, initiative petitions would be used rarely because more people would let the Legislature debate proposals and tweak them to make them better.

But he knows many won't agree with that.

"The ability to use the initiative petition process is a good thing, but I don't think it's been used well - and I think we can improve on the process," Ashcroft said. "I think the people like the idea of the citizens of the state having that escape valve, that release, for whenever the Legislature or the governor (just) won't act on something.

"And they can force that to happen."

Have a question about this article? Have something to add? Email reporter Bob Watson at [email protected].