While one math class was measuring the circumference of an Oreo, another was applying the California High School student Chromebooks to online equation solving.

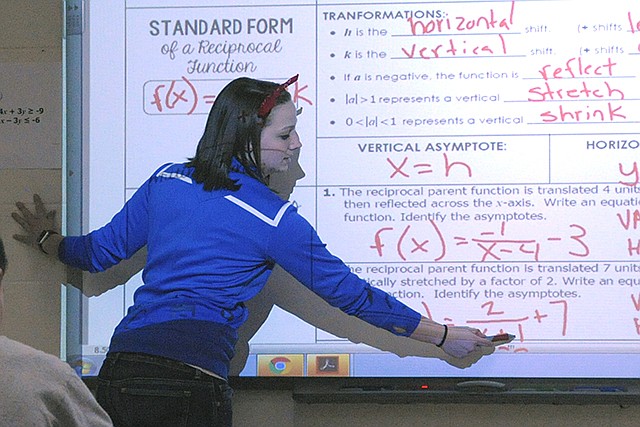

Across the hall, a third class was wrestling with the concept of graphing reciprocal functions, and a fourth was taking a quiz.

It's a typical, busy day of learning. What may be unique is all of the school's math instructors are women.

March is Women's History Month, and the recent popularity of the movie "Hidden Figures" has drawn attention to accomplishments and barriers.

These teachers, however, seek accomplishments as a team for their students and did not face serious obstacles in their pursuit of a math-related career field.

"I always knew I wanted to be a math teacher," Pinto alumni Tabatha Silvey said. This is her first year teaching at her alma mater and second in her career.

"Math came easy-ish to me, and I realized in high school I understood something that a lot of people didn't," Silvey said.

At Central Methodist University, Silvey said, only one female professor was in the math department. However, that didn't bother her.

The worst she faced was the occasional question: "Doesn't math come easier to men?"

Similarly, Ashley Banderman's experience at Hannibal-LaGrange College saw few female role models in math. "But there was no big push-back because I was a woman," she said. "In the education realm, I think we're past that."

Chrissy Yingst, in her first year at California and sixth overall, agreed: "They were just teachers; gender didn't matter."

What these teachers observed is men in math often seek jobs with power and money.

However, teaching math requires patience. That's what this team of teachers brings along with creativity and collaboration.

The California High School math department also benefited from other school-based changes, such as relocating all four math classrooms in the same area and adjusting the class schedule so all the teachers had the same planning period, Principal Sean Kirksey said.

These adjustments have allowed the team to share lessons and strategies between class periods and during planning time.

"They put the kids first, and because they have that in common, it works well," Kirksey said.

The changes are already showing results. Student scores in algebra from a pretest of course content in the fall compared with a recent pretest showed most students had double-digit gains, Kirksey said.

"The ability to share best practices makes everyone better," he said.

It also helps that they all teach algebra, said Ashley Reno, in her second year teaching at California.

Banderman noted all departments have their struggles, but "more people hate math."

"No one says, 'I can't do English!'" Silvey agreed.

As they develop ways to teach students, they're also teaching each other. Sometimes there's some friendly competition between classes.

Unlike the stereotype of a rigid math teacher, these teachers pride themselves on being approachable.

Now, they're looking ahead to ways to improve the department for future students. Perhaps that will be a class in summer school or adding a math applications class.

Silvey hopes, after she earns her master's degree, to offer advanced math classes, currently only available for college credit online.

Working as a team also has allowed the teachers to share ways of incorporating the district's new student Chromebooks.

"We're getting away from a textbook-based curriculum," Banderman said.

However, "math is still a subject you've got to write down," Yingst noted.

That's the challenge.

"We've got to think outside the box," Silvey said.