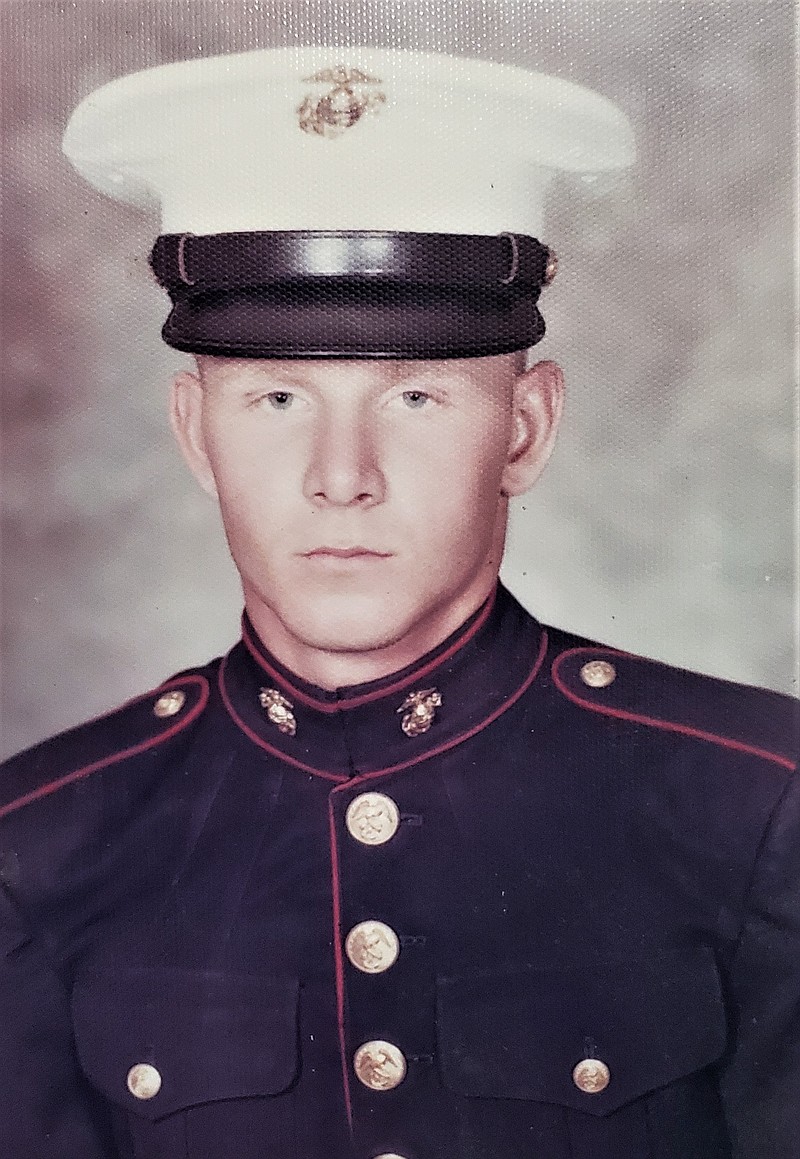

Soon after graduating from high school in Alton, Illinois, in the spring of 1970, an 18-year-old Teddy Sigite received a letter stating that Uncle Sam had plans to bring him into the military through the draft.

Instead, he and two of his friends decided to voluntarily enlist in the U.S. Marine Corps, thus beginning an adventure that introduced him to a new and innovative aircraft.

"I don't really know why we decided to join the Marines instead of waiting to be drafted," Sigite said with a chuckle. "Who knows why you did the things that you did when you were so young."

After finishing boot camp at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot in San Diego, he was sent to Camp Pendleton, California, for additional training in infantry tactics. While there, he recalls his training cycle being extended by several weeks due to an unanticipated medical development.

"We were quarantined twice because of spinal meningitis, so we ended up being there longer than normal," he said. "I can remember that we had to go to the mess hall to eat after all of the other Marines were finished and then cleaned our own dishes (to keep from exposing others)."

In the early weeks of 1971, the young Marine received orders to report to Millington Naval Air Station in Tennessee, undergoing several months of training to qualify as an aviation machinist mate. While there, he was introduced to the fundamentals of flight and basic maintenance procedures before moving on to advanced training to learn how to work on jet engines.

During this timeframe, Sigite recalled, he and other trainees were provided opportunities to work on the turbojet engines of a Douglas A-4 Skyhawk - a light attack aircraft that was initially developed for the Marines and Navy nearly two decades earlier.

From there, he transferred to his first duty assignment with a squadron at the Marine Corps Air Station at Merritt Field in Beaufort, South Carolina. Upon arrival, he soon discovered he would be working on an aircraft that had undergone its first flight only three years earlier - the AV-8A Harrier.

Manufactured by Hawker Siddeley in the United Kingdom, the Harrier became the first vertical take-off combat airplane to enter operational service. The Harrier was equipped with angled jet pipes that not only allowed it to take off and descend vertically, which negated the need for runways, but also had the ability to hover in midair.

"The squadron I was with had a very interesting composition," Sigite said. "I was in the engine department, and there were other departments such as avionics, hydraulics, ordnance. Each department," he added, "had two Air Force personnel assigned to it because the Air Force was considering purchasing the Harrier as well."

Since the aircraft was new and the Marine Corps was becoming familiar with its maintenance requirements, capabilities and limitations, technical representatives from Hawker Siddeley also were assigned to the base. Adding to the unique mix were the Marine, Navy and Royal Air Force pilots working together to learn to pilot the Harrier.

"While I was stationed there, we ended up with 45 planes in about two years," he said. "They eventually started another squadron, and they took 15 of our aircraft right off the bat to get it going."

The Harriers that were purchased from overseas were crated in sections, which were flown to the United States in Air Force transport planes. The Harriers were then assembled, and Sigite assisted in running tests on the engines in addition to performing any scheduled maintenance.

"They put on several air shows because the Harrier was so new and interesting," Sigite said. "I can also remember going out to China Lake Naval Air Station in the Mojave Desert with the squadron for about three years in a row, so that we could conduct training exercises."

Part of the squadron's training regimen included participating in maneuvers aboard aircraft carriers stationed along the East Coast. Additionally, he completed a four-month training cruise aboard a carrier that traveled to Greenland and Portugal, all the while working to keep the Harriers on board in operational condition.

In early 1974, Sigite's squadron was preparing to deploy to Japan, but since he had fewer than six months remaining in his enlistment, he was transferred to Marine Attack Squadron VMA-231 at the Marine Corps Air Station at Cherry Point, North Carolina. In September 1974, he received his discharge from the Marine Corps.

The following year, he married his fiancee, Carol, and the couple have since raised a son and a daughter. Sigite was employed for 32 years as a machinist for a company in the St. Louis area that produced bottles, insulation, shingles and associated products. In 2008, he and his wife moved to Holts Summit to be closer to her family.

"Several years ago, I saw an ad in the paper that noted the American Legion in Jefferson City was looking for some part-time help," he said. "I have been working here for several years as a cook, but I am also a longtime member of the Legion."

The time spent working with the Harriers was a fascinating experience for a young, mechanically inclined Marine. Not only did the aircraft inspire a sense of awe through its demonstrated capabilities, but revealed to Sigite the dangers associated with its operation.

"There were about three pilots that were killed while I was stationed at Beaufort," he said. "It was a dangerous aircraft, and there was no flight simulator for training, so the pilots needed to know how to fly."

He added, "But it was always so interesting to work with something that was new. The time I spent working on the Harrier opened up my ability to learn, and I soaked it all up like a sponge."

Jeremy P. Amick writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.